Triggers

I heard about this book via Cortex, a podcast discussing work (and life) habits of CGP Grey and Myke Hurley (of podcasting and Youtube fame). In the episode, they discuss the book and lay out what they both had taken home. Although Triggers falls right into the business self-help category, it seemed that the message was somehow clearer and more pronounced than in other books. So I decided to check it out.

Before you’re even on the first page of this book, you’re impressed by the praise written by some incredible people. It includes many top CEO, world leaders, and great thinkers. These are only three that stood out to me the most:

- Jim Yong Kim, twelfth president of the World Bank

- Ken Blanchard (One Minute Manager)

- David Allen (Getting Things Done)

The book, Triggers – Creating behaviour that lasts – Becoming the person you want to be, is structured in four parts:

- Why don’t we become the person we want to be?

- Hint: it’s our environment

- Try

- Hint: active daily questions

- More structure, please

- No regrets

In short, the book can the summarised as follows. It’s very hard to change your behaviour as an adult. We are influenced greatly by our environment and willpower is unlikely to help you in the long term. You’re a good planner, but your doer needs a coach to close the feedback loop. And with active daily questions, you can actively work to change your behaviour.

There are some immutable laws of behaviour change:

- Meaningful behavioural change is very hard to do

- We can’t admit that we need to change

- (e.g. my body looks fine, smoking helps me socialise, I’m fine in my current job)

- We don’t appreciate inertia’s power over us

- It takes an extraordinary effort to stop doing something in our comfort zone, in order to do something that is good for us in the long run

- We don’t know how to execute a change

- You need motivation, understanding, and ability

- We can’t admit that we need to change

- No one can make us change unless we truly want to change

- Change has to come from within

- You really have to mean it

- And you have to have buy-in from your partner or co-workers

- Behaviour change is simple, but far from easy

We have many beliefs that stop behaviour change in its tracks:

- If I understand, I will do

- There is a difference between understanding and doing

- We are confused about this difference

- Personal note: I understand so many things about startups, life, fitness, etc. But doing them is whole other thing

- I have willpower and won’t give in to temptation

- We chronically underestimate the power of triggers in our environment

- Few of us will foresee the challenges we will face

- We have overconfidence in our abilities

- Personal note: has anyone seen Temptation Island?

- Today is a special day

- Excusing our momentary lapses as an outlier event triggers a self-indulgent inconsistency which is fatal for change

- Change doesn’t happen overnight

- At least I’m better than…

- We trigger a false sense of immunity

- I shouldn’t need help and structure

- We have contempt for simplicity and structure

- See: The Checklist Manifesto – Atul Gawande

- We think we are better than the rest, we lack humility

- I won’t get tired and my enthusiasm won’t fade

- Self-control is a limited resource, that will deplete

- I have all the time in the world

- We underestimate the time it takes to get anything done

- We believe that time is open-ended and sufficiently spacious to get things done

- This will lead to procrastination

- I won’t get distracted and nothing unexpected will occur

- There will be a high probability of many low-probability events

- Example: there is a small change you will get a call from someone specific, but there is a high chance that you will get a call from anyone this week

- This will lead to unrealistic expectations

- An epiphany will suddenly change my life

- Sure it happens, sometimes

- But in most cases, it leads to magical thinking

- My change will be permanent and I will never have to worry again

- We have a false sense of permanence

- If we don’t follow up, our positive change doesn’t last

- When we get there, we cannot stay there without commitment and discipline

- My elimination of old problems will not bring new problems

- We don’t understand that we will have future challenges

- Once we are in a new situation, other problems will prop up

- My efforts will be fairly rewarded

- Our dashed expectations trigger resentment

- Getting better should be its own reward

- No one is paying attention to me

- We falsely believe that we’re in isolation

- But people always notice

- If I change I am “inauthentic”

- You stubbornly stick to your old behaviour

- You try and use that to justify why you can’t change

- I have the wisdom to assess my own behaviour

- We are notoriously inaccurate in assessing ourselves

- We have an impaired sense of objectivity

Internally we have a lot of rationalisations. But we are also unaware of how our environment shapes our behaviour:

- Our environment is at war with us

- It’s a nonstop triggering mechanism whose impact on our behaviour is too significant to be ignored

- Small tweaks in the environment can change everything

- We choose to place ourselves in an environment that, based on past experience, will trigger bad/old behaviour

- Example: bedtime procrastination, we prefer to remain in our current environment

- The environment is situational, it’s a hyperactive shape-shifter

- And a changing environment changes us

- Our environment is a relentless triggering machine

We can identify our triggers with feedback loops:

- Feedback teaches us to see our environment as a triggering mechanism

- A feedback loop comprises four stages: evidence, relevance, consequence, and action

- Behaviour follows a pattern

- You could say that it’s a complex adaptive system (The Quark and the Jaguar)

What if we could control our environment so it triggered our most desired behaviour?

Trigger: Any stimulus that impacts our behaviour

- It can be direct or indirect

- Direct: you see a happy baby, you smile

- Indirect: you see a family photo, thinking, you call your sister

- It can be internal or external

- External: from the world via our senses

- Internal: from thoughts and feelings

- It can be conscious or unconscious

- Conscious: requires awareness

- Unconscious: e.g. weather

- It can be anticipated or unexpected

- Anticipated: e.g. reaction to a song

- Unexpected: sudden realisation (falling stair example)

- It can be encouraging or discouraging

- Encouraging: maintain or expand what we’re doing

- Discouraging: stop or reduce what we’re doing

- It can be productive or counterproductive

- Productive: push us towards becoming the person we want to be

- Counterproductive: pull us away

- We want short-term gratification, we need the long-term benefit

- We define what makes a trigger productive (and encouraging)

- These last two make a quadrant of wants/needs

- Using this quadrant you can identify your habits

There is a step (impulse, awareness, choice) between trigger and behaviour.

- We are not only driven by the triggers/antecedents/cues

- See: The Power of Habit (Charles Duhigg)

- His idea: keep the cue (trigger), change behaviour (routine), keep the consequence (reward)

- With interpersonal behaviour, there is more to the routine

- Impulse: your first reaction, not always the best

- Attention: our awareness and thus ability to make;

- Choice: to react automatically or do something different

We are superior planners and inferior doers

- How is your planner going to deal with your doer?

- Measure your need, choose your style

- Directing: giving instruction, one way

- Coaching: helping, working together

- Supporting: offer support where needed

- Delegating: give an assignment, step away

- This is based on Ken Blanchard (One Minute Manager) situational leadership

- And also applies to yourself (the planner and doer)

- The planner intends to change our behaviour

- The doer actually makes change happen

We must forecast our environment

- Anticipation

- We can think, beforehand, what to do in an environment

- Avoidance

- In many cases, it’s best to avoid a situation

- E.g. don’t take the route via the supermarket when we’re hungry

- We rarely triumph over an environment that is enjoyable

- Inertia is partly to blame

- Temptation can corrupt our values

- Because of our delusional belief that we control our environment, we choose to flirt with temptation rather than walk away

- In many cases, it’s best to selectively avoid instead of always engage

- Adjustment

- If forecasting is successful (after anticipation and avoidance) we can adjust our environment

Behavioural change can happen in 4 different ways (Wheel of Change)

- Creating: when you add new (positive things). This can be stopped by inertia. You need an impulse to start adding or inventing.

- Preserving: Keep what is already working. Not messing up a good thing.

- Eliminating: Sacrifice something we like or are good at, to have something better in the future (this is difficult to do).

- This reminds me of the 80/20 rule (The One Thing), stop doing some ‘good’ things, so you can have the time to do ‘great’ things.

- Accepting: Accept reality. Don’t do wishful thinking.

How do we get to change? By trying.

One of the most important (and again, difficult) things about change is that you need to follow-up. One excellent way of doing that is by asking active questions.

Only when there were active follow-up questions, did training within an organisation work.

The format for active questions is: Did you do your best to…? or Did I do my best to…?

Here are some examples of the engaging questions:

- Did I do my best to set clear goals today?

- Did I do my best to make progress toward my goals today?

- Did I do my best to find meaning today?

- Book: Deep Work

- Did I do my best to be happy today?

- Book: Stumbling on Happiness – Dan Gilbert (TO READ&LINK)

- Finding happiness (and meaning) where we are

- Did I do my best to build positive relationships today?

- Did I do my best to be fully engaged today?

Active questions reveal where we are giving up. In doing so, they sharpen our sense of what we can actually change. We gain a sense of control, personal ownership, and responsibility instead of victimhood.

You can use the daily active questions to compare yourself against yesterday (or last week).

But beware, it’s tough to face the reality of our own behaviour – and our own level of effort – every day.

When making your own questions. Feel free to start with those above and add ones that reflect your objectives. Are you learning to meditate? Add it to the list. Want to lose weight? Add it to the list. Tired of being late all the time? Add it to the list.

The daily active questions help us in 4 ways:

- They reinforce our commitment

- They ignite our motivation where we need it, not where we don’t

- They work on intrinsic motivation

- They highlight the difference between self-discipline and self-control

- Self-discipline refers to achieving desirable behaviour

- Self-control refers to avoiding undesirable behaviour

- They shrink our goals into manageable increments

- They neutralize the archenemy of change, impatience

Daily active questions compel us to take things one day at a time.

Scores for the daily active questions need to be reported somewhere, preferably that is to someone else.

That person will be your coach. This can be a professional coach, a friend, a lover, or an accountability buddy.

The coach bridges the gap between your visionary Planner and the short-sighted Doer.

But first, you have to admit that you’re fallible, that you’re not perfect, and that you’re weak. You can’t do it on your own, and that is ok. Even Marshall Goldsmith pays someone to call him every evening and go through the daily active questions.

“When we dive all the way into adult behaviour change – with 100 percent focus and energy – we become an irresistible force rather than the proverbial immovable object.”

For the past months, I have been using the daily questions. First I had too many (for myself) and now have about 6 per day. I think that on 80% of the days I answer them and use them as a reflective moment (become the coach). I have an external coach for sports, and I (want to) share my goals with Lotte as so to better reflect on them and work towards them.

Update May 2019: I still use the system and today will update the 6ish goals. I also use a checklist for my stretches and weightlifting exercises. It’s become quite ingrained in my routine. I could do it a bit better by completing it at the beginning of the evening/at the end of activities and not before I go to bed (when I sometimes forget to do it).

Update August 2020: Still using the system, and doing it every day. Have updated it several times and still very happy with the format.

Update December 2020: Still going strong, daily. Updated it today and now at 8 questions that provide a feedback loop for several aspects of my life.

Update January 2024: Still doing (nearly) daily check-ins with slowly (every 2-3 months) changing questions. It just works.

Brick by Brick

Dive into the world of Lego with Brick by Brick by David Robertson and Bill Green. This compelling book takes you on an adventure through the recent history of Lego. It’s written in 2013 and takes the closest look at the 15 years preceding that year. It’s here where the company loses focus, tries to innovate too much, and start haemorrhaging money. But the company does find its way back (into the living room of kids) and is now seen as a powerhouse of the toy industry.

The 7 Truths

- Build an innovative culture

- Become customer driven

- Explore the full spectrum of innovation

- Foster Open Innovation

- Attempt a disruptive innovation

- Sail for Blue Oceans

- Leverage diverse and creative people

These sound pretty good, right? Well, they were almost the end of the whole LEGO empire. And what I took home most from the book is that they tried to do too much at the same time. They tried to make something similar to Minecraft (and that didn’t work because of their demands, not perse because of Minecraft’s competition). And the company forgot what their core competence was (the LEGO play experience, with the brick at its core).

Another central theme of the book was the neglect of the customer. LEGO didn’t listen to what the customers wanted. They even actively disengaged with adults who bought LEGO (which accounted for 15% or more of the sales). Only with much reluctance did they involve the customer in the development process. And at a level, I can relate to LEGO. It’s sometimes difficult to receive honest feedback. Both emotionally (you don’t want to hear it), and more basically (the customer doesn’t always know what they want or how to articulate that need). But it’s definitely something to remember and do.

Brick by Brick is a great look inside this iconic company. It’s more an examination than a book full of lessons. And that is alright. Read it if you’re interested in LEGO and innovation.

Against Empathy

In Against Empathy by Paul Bloom, we get to take an exciting look into what it feels like to take an unpopular stance. The book makes the moral case for compassion. And more than that takes on empathy (feeling of others’ emotions) on as the enemy. It’s a very interesting book that has already sparked some interesting conversations.

Use your head, not your heart

This is what I think gets the most pushback. You may ask, ‘why not use my heart, that is what makes me a moral person!’. And I totally get that. That is also how I would react instinctively. Wouldn’t we all start killing each other when there is no more heart involved? Bloom argues for a no.

One of the main arguments he puts forward is that empathy has a spotlight effect. We focus on certain people, in the here and now. Empathy is not what will lead you to donate malaria nets or make you care about climate change (how would you even see or feel that). Things we should very much care about are not touched upon by empathy. Compassion and rationality, Bloom argues, is much better at this.

Here it is in Bloom’s words:

“Empathy is a spotlight focusing on certain people in the here and now. This makes us care more about them, but it leaves us insensitive to the long-term consequences of our acts and blind as well to the suffering of those we do not or cannot empathize with. Empathy is biased, pushing us in the direction of parochialism and racism. It is shortsighted, motivating actions that might make things better in the short term but lead to tragic results in the future. It is innumerate, favoring the one over the many. It can spark violence; our empathy for those close to us is a powerful force for war and atrocity toward others. It is corrosive in personal relationships; it exhausts the spirit and can diminish the force of kindness and love.”

So you are forewarned, read this book at your own peril (but do very much read it).

Some more notes

- Bloom is not against morality, compassion, kindness, love, being a good neighbour, being a mensch, and doing the right thing

- He defines empathy as: “The act of coming to experience the world as you think someone else does.”

- Many moral actions require no empathy for you to act (e.g. saving a drowning child)

- Empathy may block you from taking action, or start avoiding the situation (e.g. beggar on the street, woman who lived next to Nazi camp)

- Empathy can make you do acts that are unfair (e.g. experiment where asked to feel like ill girl in line, people moved her up, ahead of more sick children)

- “If you absorb the suffering of others, then you’re less able to help them in the long run because achieving long-term goals often requires inflicting short-term pain.”

- Psychopaths may very well have empathy. Their folly is a lack of moral guidelines and self-control

- We can ‘read’ another person’s (or dog/cat) mind without having to feel their feelings

- The ‘identifiable victim effect’ shows how empathy can only extend to one person (and if you show more, or numbers, people tune out)

- In general, we care most about people who are like us (and from a Selfish Gene standpoint we can see where that comes from)

- And we care about things that catch our attention (e.g. saving a dog from a well and that costing $27.000, that is more than needed to save a life)

- Good parenting involves moments where you let your kid(s) suffer a little (e.g. not giving them the second ice cream)

- Foreign aid can backfire in many ways (e.g. ‘orphans’, dependency of economies)

- Both liberals and conservatives make emphatic appeals

- Compassion is feeling for the other, and not feeling with the other

- Evil in the world is not done by moral monsters (they don’t exist), it’s done by people who think they are doing the right thing

- Empathy (for your group) can motivate violence (against the other group)

- We are often irrational beings (see Thinking, Fast and Slow)

Stealing Fire

Stealing Fire by Steven Kotler and Jamie Wheal explores the concept of ecstasis. What is that? You may ask. It’s the moments you step outside yourself. It’s when you’re taking out of your rut and you feel alive. It’s what extreme sports enable. It’s why people take psychedelic drugs. And it’s what Kotler and Wheal have been searching for in the past few years. The book is very interesting to read, sometimes light on science, but high (pun intended) on aspiration and futurism.

STER

The book expands on ideas proposed by Csikszentmihalyi (Flow) and Kotler (The Rise of Superman). They take flow, a state of concentration or complete absorption with the activity at hand and the situation, and elevate it even further to ‘STER’.

- Selflessness: (partial) loss of ego or executive function

- Timelessness: attention is driven to the present (and you’re not wondering about yesterday/tomorrow, which in most cases is less enjoyable to do)

- Effortlessness: it all seems easier because of a mix of chemicals in your brain (norepinephrine, dopamine, endorphins, anandamide, oxytocin, serotonin)

- Richness: because there is more focus on the now you see more patterns, connections, ‘umwelt’, there is more processing of the now

Kotler and Wheal also discuss why we haven’t done more already in exploring these types of states. They argue that it’s because of the church (but you could argue that revelations that started religions were inspired by ecstasis states). Another reason is how we look at our bodies and that using external tools is cheating (but if you take this view, eating itself is cheating). And finally that the state prohibits experimentation and ecstasis experiences (banning drugs, dangerous sports, etc).

The 4 Forces to Ecstasis

Stealing Fire is full of examples of how we’re progressing and finding out new ways to achieve ecstasis. The authors state that there are four main drivers/areas of new discoveries:

- Neurobiology: we are getting better at understanding what is going on in our brain. What is the influence of certain drugs, states, activities? We can almost measure these things in real-time

- Psychology: take the learnings from 10 years meditation and condense them into a few weeks. Promises like that are starting to emerge from the field of psychology.

- Technology: neurofeedback, sharing experiences, virtual reality. With technology, the advance and sharing of ecstasis will be able to spread exponentially.

- Pharmacology: there are recipe books out there that help us better explore our own minds. And at the same time drugs are being used in a better way to treat mental diseases.

I listened to the book and I think that was the right choice. But for taking notes/making this summary it’s less useful. One thing I will be taking away (doing now) is the Hedonic Calendar. It’s their way of looking at ecstasis and how much you should be seeking it. It shouldn’t be that you’re always trying to lose yourself (your executive function isn’t there for nothing), but that you do it responsibly and in a way that enables learning and development.

Daily activities:

Meditation

Morning Stretches

Read

Weekly activities:

Crossfit x3

Few drinks

Bedtime x3

Monthly activities:

–

Bi-monthly activities:

Mind expansion

Annual activities:

Vacation x2+

Mega sports challenge

Gut check (no substances):

November

May

Additional checks:

No more than 1x p/month mind expansion & more than a few drinks

First entrepreneurship, then relationships, then fun

Make Haste Slowly!

The Left Hand of Darkness

The Left Hand of Darkness – Ursula Le Guin

An interesting book that first didn’t grab my attention (lots of jargon and names) but which later on proved to be interesting to listen to. Here is my analysis of the story structure.

1. You (situation, comfort)

Genli Ai is the protagonist. She is an ambassador (envoy) from a new planet. This planet is full of people who don’t have a single sex (but can become either once every 28 days). He (although the book is narrated by a woman, so sometimes you forget that, and that might be part of the experience of the book) wants…

2. Need (want something)

… to get the states of the world (Gethen) to join the alliance/federation of planets.

3. Go (new situation)

He talks to the king and is in a place he can’t call home.

4. Search (progress, adapt)

He has to travel the planet and talk to many people. The same goes for his friend (the former prime minister). And Genli learns a lot about how they live and interact. The end is foreshadowed by fore-tellers.

5. Find (no turning back)

After much struggle there is a plan to get the ship to land and the world to join the federation.

6. Take (trouble, pay a price)

But the road there is a long struggle and his friend dies.

7. Return (go back to where it started)

He returns to the capital and finalises his plan.

8. Change (now capable of change)

He is changed by his experience. And the world there is also about to change.

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress

Sticking with the last sci-fi review of Speaker for the Dead, here is another analysis of a classic of the sci-fi literature. An analysis of The Moon is a Harsh Mistress by Robert Heinlein.

1. You (situation, comfort)

We’re on the moon. And we’re following the adventures of Manuel (“Manny”), a supercomputer (Mike), and their rebel friends. The introduction does a great job of describing where we are, what is different from ‘our’ world and not focus too much on the logistics of a moon colony.

2. Need (want something)

Manny needs to break free from the Warden (the local authority figure). He wants to live free. A secret organisation is started.

3. Go (new situation)

Government is overthrown.

4. Search (progress, adapt)

Now they have to scramble to become a state in their own right.

5. Find (no turning back)

They go to earth to try and convince others they are the real thing. This phase (5) is the opposite of the start (1) and true in every way. They are not on the moon anymore, they are being diplomats (not technicians).

6. Take (trouble, pay a price)

The world isn’t listening to diplomatic channels. So a raid and bombings are on the way. “There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch!”.

7. Return (go back to where it started)

Finally, earth recognizes their independence. They are cheered on by the crowds on the moon.

8. Change (now capable of change)

Manny withdraws from politics. Mike stops talking. They are now a free state, but some things are just the same again.

Solve for Happy

Solve for Happy by Mo Gawdat is a book that delighted at times, full of anecdotes and very frustrating at other times. It’s a book that describes a mans search for happiness after his son suddenly dies in a car accident. It’s a book that is very personal yet also full of references to scientific literature. It’s a book that speaks many truths that we might forget in the busyness of that thing we call life.

Formula for Happiness

Here it is, the formula for happiness. Happiness = your perception of events in your life – your expectations of life. That’s it, easy as that. Life plays itself out in your head, it’s a battle between what you expect and what you get. If you get more than you expect, you are happy. If you get less than you expect, you are unhappy. It’s the thoughts that make us unhappy (and it’s the thing we can change) and not the events.

Most of our suffering is useless. Physical pain is very bad and really hurts. But most pain we experience is the pain we give ourselves. It’s unnecessary and leads to nowhere. So, in this moment, choose not to suffer. Choose to be happy. Accept life for what it is, and embrace it.

6 Illusions, 7 Blind spots, 5 Truths

Gawdat wants to teach us that between us and happiness, there are a few obstacles. And I couldn’t agree more with his analysis of the illusions we keep on telling ourselves.

- Thought: You are not the thoughts you’re thinking. You can (with some restrictions) control what you’re thinking.

- Self: You’re also not your body. Or emotions. Or heritage. Or religion. Or name. Or past performances. Or your things. You’re the observer, the person who sees it all. “In a world without an ego, where it doesn’t matter how everyone else sees us, we will do our utter best and get the results without caring what others think.

- Knowledge: You’re not what you know. What we know is just an approximation of the ‘real’ truths. There are many unknown unknowns still to be discovered. Real knowledge is knowing what you don’t know (Confucius).

- Time: Mechanical (minutes/hours/etc) time is made by man. Happy emotions are linked to the now, bad thoughts are linked to the past and future. If you want to be happy, live in the now.

- Control: You’re not in control of your life. Unexpected events (black swans LINK TALEB?) rule our lives. Don’t expect control, but do your best anyway (take responsibility).

- Fear: Admit that you have fear, then face it. If you hide from fear, it will only breed more fear, anger, hate, and suffering. What is the worst that can happen (LINK TIM FERRIS TALK)?

Our blind spots have helped us as a species for the last few million years. See a leaf move, think tiger, survive. Acting on a possible threat was a good strategy. But in our ‘normal’ day-to-day, there is no need for these blind spots anymore.

- Filters: Your brain filters out much information, otherwise it would be overloaded.

- Assumptions: Our assumptions are nothing more than a story our brain makes, not reality.

- Predictions: Predictions are only stories made by our brain about the future.

- Memories: Your memories are only a reflection of how you see the past (they are far removed from facts).

- Judgements: You judge before you know the whole situation (thus preventing you from making a correct assessment).

- Emotions: Our perception of reality is clouded by irrational emotions.

- Exaggerations: We have an availability heuristic and exaggerate what we see.

It’s not reality that shapes us, it’s the lens through which we see the world. So let’s take a look at how to better look at our world.

- Now: When people were asked what they were thinking about (past, now, future), results show consistently that they are happier when they’re living the moment. Connecting with others in the present is one of the best things to do. To get to the now, you have to stop doing other things (e.g. thinking). Stop doing, just be. Be here in the moment, that is where life is happening.

- Change: Change is the only thing we can predict with certainty. So go with the flow, know what you can influence, let other things go. Find the way of least resistance. Be more grateful, less greedy (or ambitious).

- Love: Unconditional love is one of the most beautiful and universal things you can offer the world. The true happiness of love is to give love. The more you give, the more you get back. Love yourself (self-compassion). What you give, you get back many fold (also see Give & Take by Adam Grant). Choose to be nice, not right.

- Death: Everyday we’re dying a little (it’s a process, not an event). Without death, there would be no life. When our body dies, the memories of you can stay for centuries. Death is unavoidable, life is now. So live before you die.

- Design: So here is where my opinions differ from Gawdat. He argues that life on this planet could not have come to fruition in any other way than by design. There must be a creator for all this to work. I would argue that life has come out of this randomness. And yes we don’t exactly know how, but you don’t need a creator to explain the processes by which evolution, human interactions, and the individual processes are moving.

Speaker for the Dead

Something different this time. Instead of a short review, an analysis of the story structure of the most recent sci-fi book I’ve read. The book in question is Speaker for the Dead by Orson Scott Card. It’s partly based on this essay/guide by Dan Harmon.

1. You (situation, comfort)

This part is for establishing the protagonist. This takes a while because we first get a deep dive into the world (which is maybe partly the protagonist, in an abstract way). There we follow two people who will later on die. Ender, the main character, only arrives (literally) later on.

It does establish the world we are living in (how long after Enders’ Game), which planet, what species.

2. Need (want something)

The thing that is not perfect is that the piggies (the other species on the planet) and humans need to live together. And change is happening, piggies are learning.

At the same time, a need is that for Ender (as Speaker for the Dead) to come speak the death of the xenobiologists. This is the actual call for adventure.

3. Go (new situation)

Ender is on his way in his spaceship. He has crossed the threshold, said goodbye to his life-friend (his sister). Or the go could be at the killing of the first xenobiologist.

The story goes from peace/observation to action and possible conflict.

4. Search (progress, adapt)

How can we communicate with the piggies? What story needs to be told here? Why were the xenobiologists killed? Who can we trust? Ender and others go on a search for the truth.

5. Find (no turning back)

Ender meets with the piggies.

6. Take (trouble, pay a price)

Congress (world government) is not happy. Rebel or sentence two people to years in prison. Option 1 is chosen. They meet with the female piggies.

Ender gets things done. Negotiates with the three living species and finds a way to get everything rolling.

7. Return (go back to where it started)

A new peace is established after much negotiation.

Ender gets his sister involved. They are a team again.

8. Change (now capable of change)

Truth has been found. The sermons have been spoken. The team is back together (with some new friends).

Blue Ocean Strategy

Blue ocean strategy is the simultaneous pursuit of differentiation and low cost to open up a new market space and create new demand.

I’ve heard about the blue ocean strategy from many people, and at multiple times. And the above description is about as much as I knew about it. Get away from the competition, and make your own (new) market. That sounds very positive, but how is it done?

This is my overview of the schemas from Blue Ocean Strategy by Renée Mauborgne and Chan Kim.

The BLUE Ocean

Where most companies compete is also where most companies are. They are competing against each other for the same attention of the same customers. If this market is a pond, it’s one that is very full. And it’s competitive if companies are fishes, some might even get hurt. The red ocean is the current (know) market.

Where the bulk of the profits are made, is where the least amount of companies are. This is in markets that don’t even exist today, they are unknown. Imagine yourself on an expedition around the world and you find a body of water that no person has ever been on. You’ve found yourself a blue ocean. Here there a no boundaries, rules, or competition.

You can get yourself into a blue market by making a strategic move. There is no ‘blue ocean’ company, but there are products that companies launched (via a strategic move) that swam in a blue ocean for a very long time. There are very few companies that have been able to apply the blue ocean strategy multiple times.

How can you be one of these companies? How can you make a strategic move that leads to a blue ocean?

VALUE Innovation

Value innovation is a dedicated focus on making the competition irrelevant by offering exceptional value to your customers, whilst keeping your own costs down. If you create value without innovation you are probably only providing a little more value for your customers (e.g. the new iPhone). If you create innovation without a direct value for customers you don’t have a market (e.g. Virtual Reality in the ‘80s/now?). If you combine both, you create something people want (e.g. the original iPhone, Tesla Model S, Cirque du Soleil).

Value innovation is the combination of improving your cost structure and providing customer value. You decrease your costs by not doing and minimizing the things that most of your competitors focus on. And you improve the value by doing and raising something your competitors don’t focus on.

Blue Ocean TOOLKIT

To innovate where others are competing you have to know how to identify what is a value innovation. For this purpose, you can use the following tools: The Strategy Canvas, The Four Actions Framework, Six Paths Framework, The Buyer Utility Map, and The Price Corridor of the Mass. Yes, these are quite some tools, so get ready for a short explanation of each one. The tools are sequential and normally the next one builds on the insights of the previous tool.

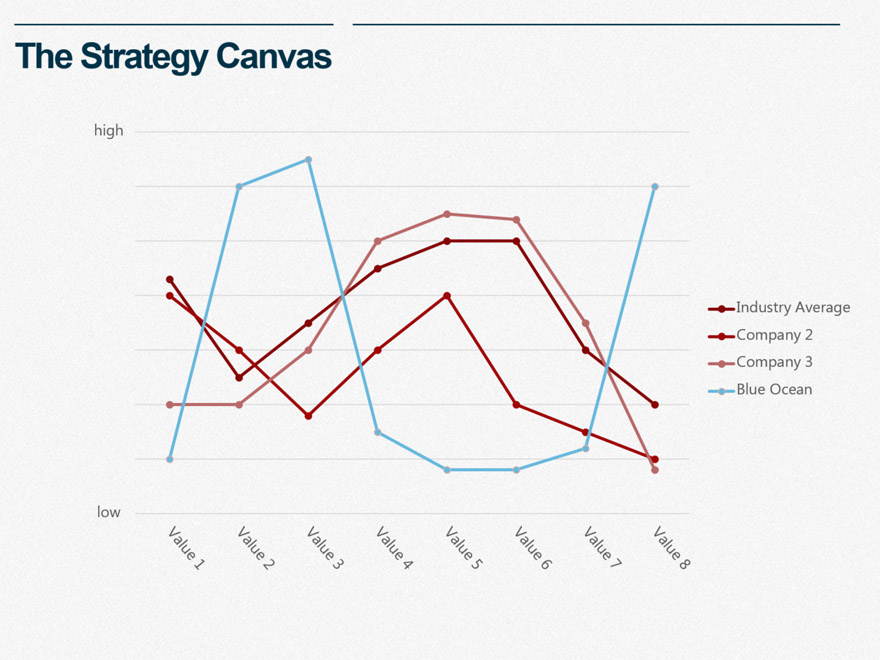

The Strategy Canvas

Use the strategy canvas to identify where you do things different from your competition. To do this you should identify all the competing factors on which you operate. Some examples are; price, marketing, location, star performers, service. Here is an example of the strategy canvas. Note that you can best use this framework at the beginning (where your line might look like that of the competition) and at the end (when it should look very different).

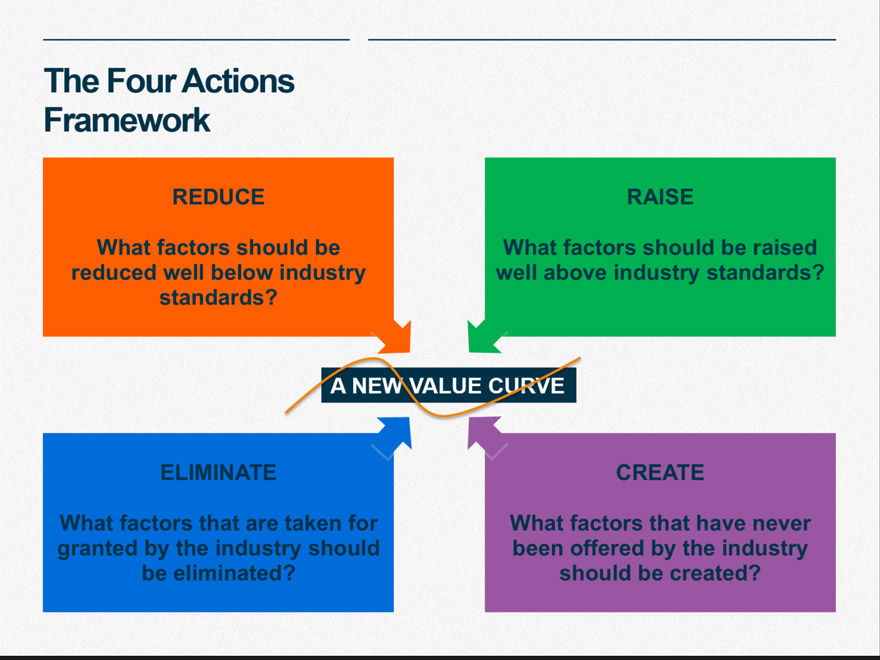

The Four Actions Framework

Use the Four Actions Framework to identify which things you should eliminate, reduce, raise, and create. You need to know what your unique buying reason (UBR) should be for your customers, in what way are you different from the competition. And what things are the competitors doing that makes no sense (e.g. explaining wine in fancy terms to people who just want to drink something tasty).

The Four Actions Framework helps you to increase your focus, diverge your value curve and define your tagline. You pick one place on which you focus your efforts. You add value to your customers on something that others are not. And you summarize this in your tagline, preferably something that’s catchy.

The Six Paths Framework

Use the Six Paths Framework to redefine where your product is competing. On six dimensions you can ask yourself a new question. Instead of looking at the competition within an industry, ask yourself what you can do with your product in another industry. Instead of looking at a trend and adapting to it, why not create a new trend yourself?

| Head-to-Head Competition | Blue Ocean Creation | |

| Industry | Who are my rivals within the industry? | What other industries can I go to? |

| Strategic group | Where do I stand within this strategic group? | Which strategic group can I enter? |

| Buyer group | How can I better serve my customers? | Who are other people that I can also serve? |

| Scope of product or service offering | How can I provide the best value within this industry? | How can I use other products/services from other industries in my offer? |

| Functional-emotional orientation | How can I use emotion or function the best? | How can I use emotion or function in a different way than normal? |

| Time | How can I adapt to a trend? | How can I shape a trend? |

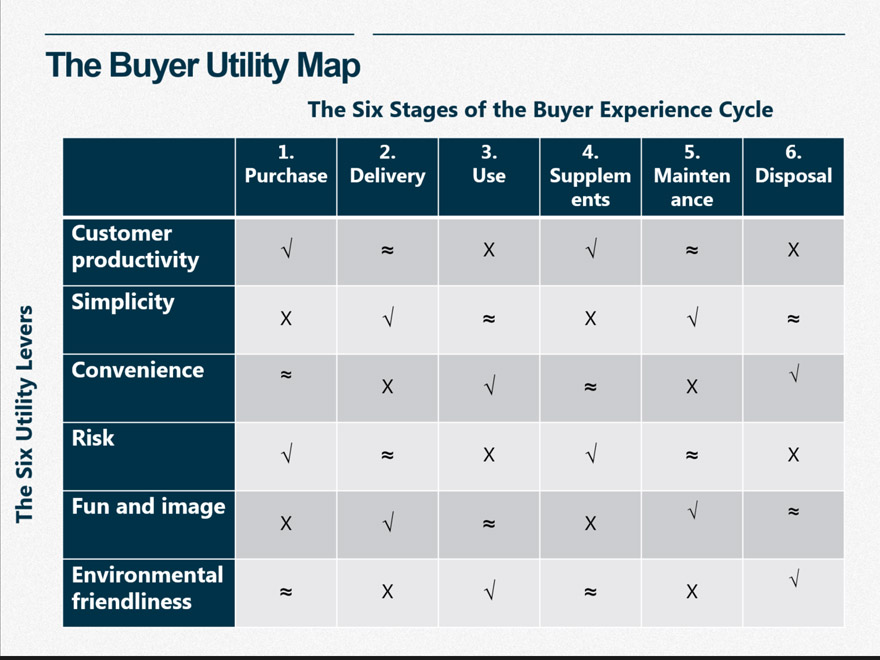

The Buyer Utility Map

Use the Buyer Utility Map to identify blocks to providing utility to your customers. In each step of the use of a product (from purchase to disposal) a customer is assessing it on various dimensions. This ranges from their own productivity to the environmental impact of the product. The more places you can check off, the better.

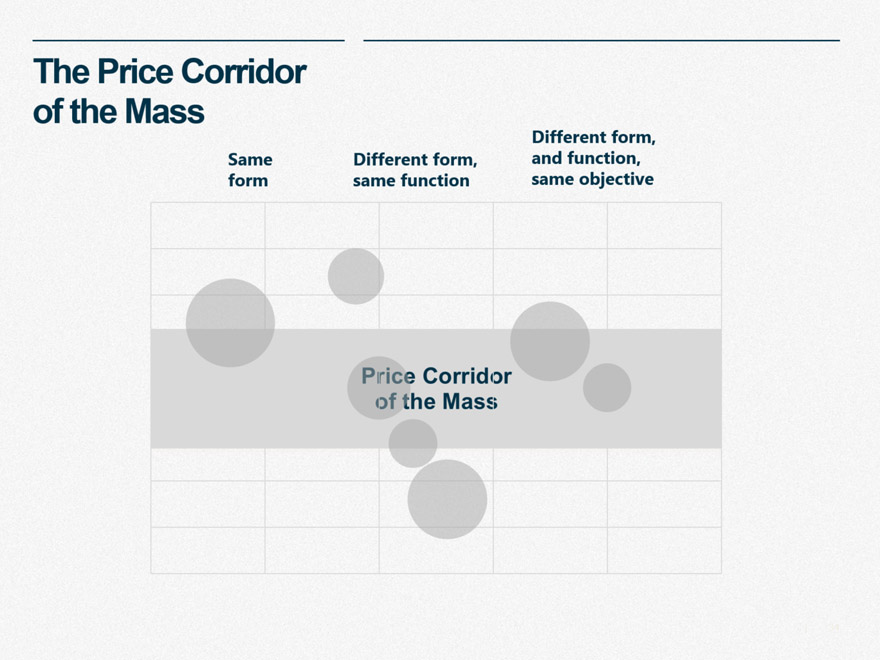

The Price Corridor of the Mass

Use the Price Corridor of the Mass to define at what level you can price your product. In this tool, you can define at what level your competitors (within your market, but also similar markets) price their products. You can then price your product 1) higher, 2) in the middle, or 3) lower. This all depends on how unique your product is. If it’s new but easily copied, maybe price it low to keep competition away. If it’s very difficult to replicate, price it high.

Your price should mainly be defined by ‘target costing’. This means that you use the strategic price (found via the price corridor) and deduct the desired profit margin. What is left is the target cost. By going in the opposite direction from normal pricing, you will be more likely to find novel ways of keeping your costs down (e.g. innovation in price model, partnering, operational innovations, etc).

SUSTAINABLE Blue Oceans

Creating blue oceans is not a static achievement, it’s a strategic process that needs to constantly be updated. The toolkit as presented here is only a start and using it is the only way to create new blue oceans.

In your pursuit of value innovation, there will always be imitators. Their strength and duration before they arrive are highly dependent on how easily they can copy your formula. And when the competition gets near, update your value curve, eliminate, create and stay relevant. There are no permanently excellent companies, but there is a blue ocean strategy that you can follow!